Challenger

One ugly day

January 28, 1986

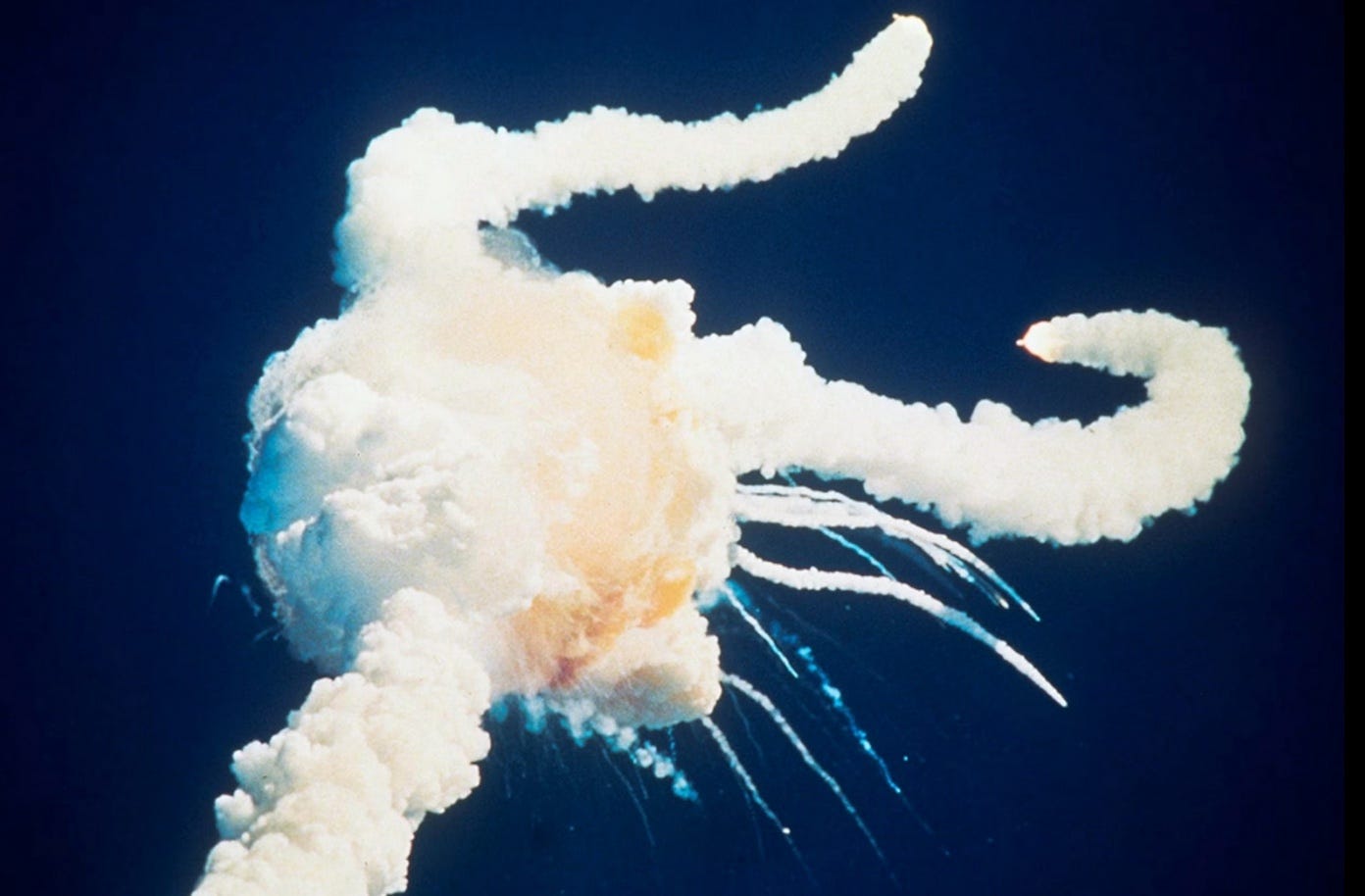

Forty years ago this week, the space shuttle Challenger exploded over the Atlantic ocean seventy-three seconds after liftoff, killing all seven crew members, including Christa McAuliffe, the first to fly in a Teacher in Space Project designed to “inspire students, honor teachers, and spur interest in mathematics, science, and space exploration.” (Wikipedia)

That this is all sepia-tinted history to the current generation is understandable. I felt the same way about the Hindenburg disaster — a horrific tragedy that happened in 1937, well before I was born — but having grown up during the ‘50s and ‘60s enthralled by the race to put a man on the moon, the Challenger explosion hit hard.

Given the early history of NASA — rockets blowing up with disturbing regularity — the risks of spaceflight were obvious. Unlike the Soviet space program, the US had never lost an astronaut in flight, but three of our own died in a terrible fire during a routine test on the launchpad of Cape Kennedy in 1967. Still, there were several near misses. During two of the early orbital missions, manned capsules began tumbling out of control, with disaster averted only by the courage, level-headedness, and skill of those test-pilots-turned-astronauts. Lesser men would not have survived those ordeals.

Thanks to the astonishing success of the Apollo program, spaceflight began to lose some of its luster in the public eye. Flying to the moon and back almost seemed normal until the aptly-numbered Apollo 13 mission, during which three astronauts barely survived a harrowing ride around the moon and back after an explosion destroyed a fuel cell supplying electricity to the craft two days after liftoff. But after the next four lunar missions went without a hitch — including taking along a car to extend the astronauts range of exploration — landing on the moon no longer felt quite so special.

Then came the Space Shuttle, a “space truck” designed to fly once a month carrying satellites (including the Hubble telescope) and crews into orbit to build the International Space Station. It worked so well that orbital missions began to feel routine, but nothing about space flight is “routine.” Each mission was a high-risk endeavor in which pretty much everything had to go right to succeed, and where the immense forces involved meant that when it came, failure was catastrophic.

I was working on a crew filming a Burger King commercial down in the South Bay region of LA on the morning of January 28, 1986. Thirty young children were there as extras, and with the first teacher in space scheduled to fly, the production company brought in a big color monitor so the kids could watch the launch while we filmed a few exterior shots. By then I’d seen so many launches that I didn’t bother to go in when the time came — being anxious to prove to the gaffer and best boy that I was a pro, I remained outside with the big carbon arc lamp I’d been hired to operate. The gaffer went in to watch, but came out a minutes later looking grim.

“The space shuttle blew up,” he said, then walked away.

I couldn’t believe it. Having built and flown my own rockets as a teenager — real rockets made of aluminum and steel, loaded with home-brewed fuel mixed down in the basement or on my mom’s stove — I knew the difference between solid and liquid-fueled rockets, and that it was highly unlikely that the shuttle itself could “blow up.” I went inside to watch the replays, where I saw it was the huge external fuel tank carrying liquid hydrogen and oxygen that had exploded, not the shuttle — but that was a distinction without a difference: those six astronauts and Christa McAuliffe were just as dead.

The teacher, kids, actors, and production people inside the store were in a state of shock, but it was only 8:40 in the morning, and we still had a commercial to shoot … so we did. I’m sure most on the crew felt like me — I’d never spent a day on set that felt so utterly empty and meaningless — but this was our job, so we soldiered on through.

We wrapped as darkness fell, then went our separate ways home. My drive was a brutal stop-and-go slog back to Hollywood that took more than an hour, all but blinded by oncoming headlights the whole way. Traffic moved faster as I headed up La Cienega, where a cat suddenly darted across the road silhouetted in all those headlights. A car swerved but hit it, and cat spun, tumbled, and jumped in violent spasms like a demon from hell before being crushed under the wheels of another car. It was a shocking, horrifying sight.

I like cats. I like dogs. I like animals in general, and hate to see them suffer … and after witnessing so much violent death and misery that day, this felt like the final straw. It was awful.

I finally made it home, where I inhaled a stiff drink, then another, but it wasn’t enough. An ocean of whiskey wouldn’t have helped that night. It had been an unfathomably ugly day from start to finish, one of many in my life, beginnng with the assination of JFK, his brother Bobby, Martin Luther King, 9/11, the Columbia disaster, and the current political pit our country is in. It’s been a long bloody sixty-plus years under the shadow of so many catastrophes … and I have to wonder: do they ever stop?

Late in life, I finally understand why old men silently stare into the fireplace, watching the wood go up flames.

Certainly feels grim globally at the moment…

Great piece, Michael: Indeed, tragedy after tragedy. That's the experiment we're in sadly. To see animals suffer kills me. I would have had to consume the entire bottle of whisky after that day.