When I was in school making student films back in the Pleistocene, my assumption was that working on movies in Hollywood would be a completely different experience. While student films were a one-step-forward/two-steps-back circus of earnest, enthusiastic ambition hobbled by boundless ignorance and confusion, Hollywood productions would be run by seasoned pros who knew how to make each day’s filming on set unfold in a smoothly efficient manner. My assumptions further concluded that the classic films which lured me to the world of film — Casablanca, The Wild Bunch, The French Connection, Chinatown, and The Godfather — must have been a pure pleasure to work on, right?

Yeah … about that. Despite forty years of first-hand experience in just how fucked-up a Hollywood film set can be, the romantic (read: hopelessly naive) illusion that those classic films were somehow blessedly immune from the maladies plaguing all forms of filmmaking lingered in my mind. It’s only now that I’m comfortably ensconced on the sunny beach of retirement that I’ve learned the truth: working on every one of those films was a bitch.

This revelation came from the venerable form of self-education known as “reading books.” Yes, I know … reading printed books is no longer fashionable in these modern screen-addicted times, but I’ve reached the point in life where the socio-cultural whims du jour are a matter of indifference. When I’m not outside shaking my cane and yelling at passing clouds, I even listen to CDs and watch DVDs — so, yeah, I’m a full-on dinosaur.

My latest this-is-how-it-was read is Leave the Gun, Take the Cannoli, by Mark Seal, and it’s a good one. If you’ve read Bob Evan’s memoir The Kid Stays in the Picture or seen The Offer, a ten-part drama about how The Godfather was made, you know something about it, but Leave the Gun, Take the Cannoli goes deeper without stretching the truth for the sake of pumping up the drama. It’s very well written, and a great read for any fan of The Godfather in particular, of movies in general, or anybody who like to surf waves of gorgeous prose.

I hadn’t seen the movie since it first hit theaters in 1972, more than fifty years ago, so after reading the book, I pulled out the DVD and slipped that shiny disc in the player. Although it didn’t feel quite so monumental as it had on that warm summer afternoon so long ago, The Godfather is still a damned good movie — and having learned how hard it was to get that film from book to screenplay to screen made it all the more impressive. I dunno … maybe there’s a connection between how difficult a particular movie is to make and the quality of the finished product. As the old adage holds: “It takes a lot of pressure to turn a lump of coal into a diamond.”

On the other hand, consider a phrase I heard on set more than once: “It’s just as hard to make a bad movie as a good one — so let’s make a good one.” Alas, we failed most of the time in that noble quest. So it goes.

As for reading about those other classics, I highly recommend the following books — they’re all terrific:

*****************************************************

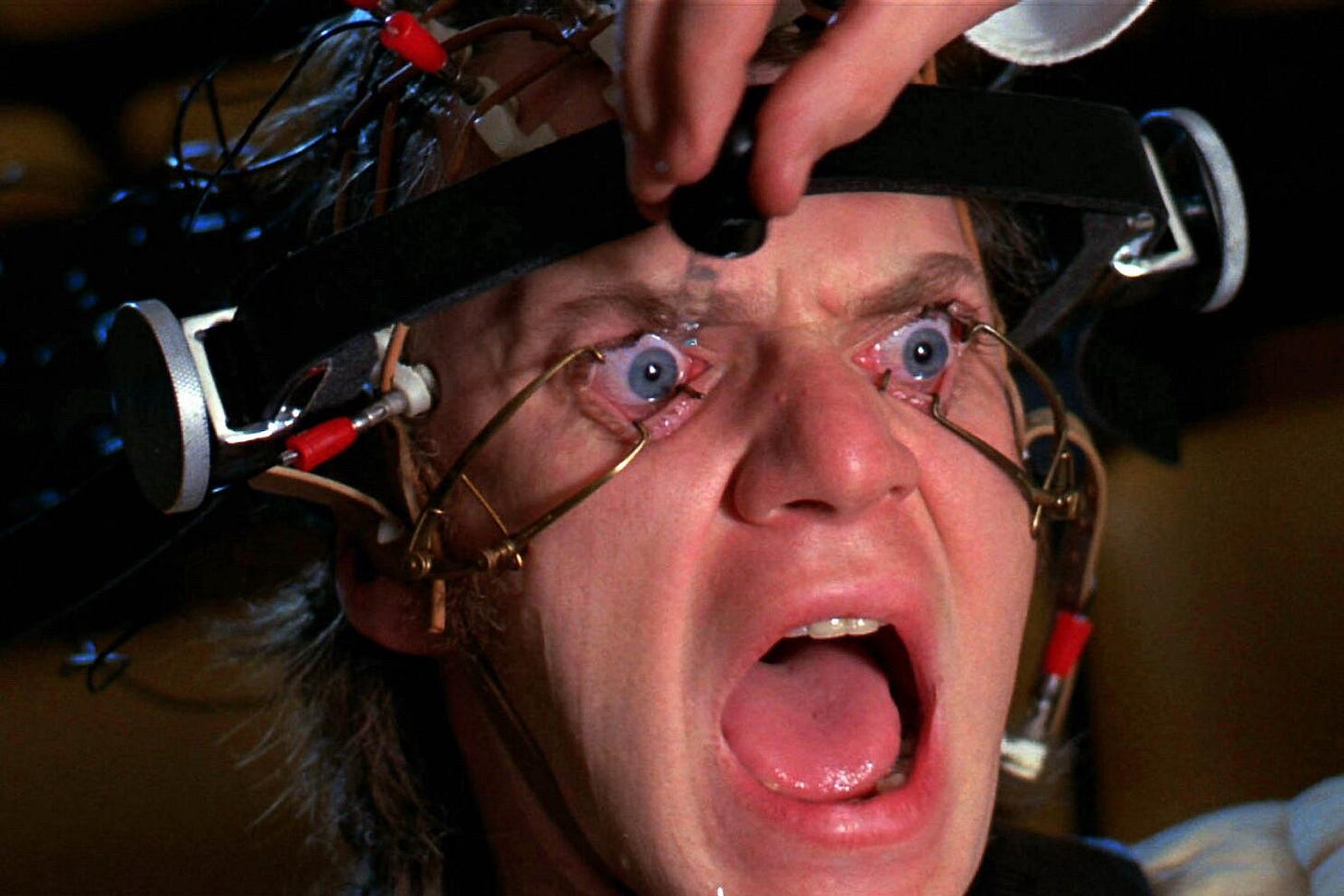

The single-take aesthetic has long had adherents among a small cloister of cinephiles deluded enough to declare that Hitchcock’s Rope — the first long-take feature film I saw — is actually a good movie. Rope is an interesting experiment in crafting a film that appears to be shot in one uninterrupted take — a feat impossible with the technology of the time — but it’s light years from being a good movie. I found it an insufferable bore: a stage play turned into a movie that embodied all the worst aspects of live theater while pointedly ignoring the advantages of film. As evidenced by Twelve Angry Men, a truly great film can be made with a small cast in a single room, but Rope doesn’t measure up … at all. Even the masters occasionally fall flat on their face, so with all due respect to the great Alfred Hitchcock, the only way I’d watch that movie again is if I was strapped to a chair like poor Malcolm here.

The next long-take feature I became aware of was Birdman, but being perennially behind the times, I have yet to see it, and thus can’t say whether the single-take technique works for that film or is just a gimmick.

Now comes a four-episode show from Britain — each segment an hour long — called Adolescence that also follows the single-take muse. I watched the first episode and was seriously impressed with the astonishing human and technological achievement of shooting a multiple-location, sixty-five-minute drama in one take — without so much as a single cut — but wasn’t entirely convinced that it qualified as “entertainment.” The initial episode opens with a grim story about a terrible thing that happens to two working-class families in England, a tale that in many ways feels all too real. Truth be told, I wasn’t sure I wanted to watch any more … I mean, it’s extremely well done, but given that we’re currently living in a world that seems to be collapsing on itself and going up in flames, “grim” doesn’t necessarily check the “that’s entertainment” box of my watch list.

Maybe that’s why I tuned in this podcast interview with Steven Graham, the British actor playing the father of the young boy who’s the focus of that first episode. The meat-and-potatoes character Graham portrays is a blue-collar guy, stocky and muscled, without a lot of nuance, but he loves his son and can’t understand how or why the young boy — who’s just a kid — is being held by the police on a charge of murder.

Until listening to that podcast, I had no idea Graham had a big role in getting this show made and on the air. It turns out he’s not so much interested in who did what — the dramatic thrust of most police dramas — but why it happened. I don’t yet know if the series can or will answer that question, but after hearing Steven Graham talk about it for forty-five minutes, you bet I’ll be watching to find out.

In a recent piece for the San Francisco Chronicle, critic Mick LaSalle discussed the aesthetics and relative impact of shows that simulate a single-shot technique by using post-production technology — in other words, cheating — and the real deal like Adolescence.

“There’s a difference between faking it and really doing it. Part of the distinction is our own response. If you’re watching a trapeze act, it’s just more exciting if there’s no net. The longer a shot goes on, the more pressure there is on the actors not to blow it, and I believe we as viewers can pick up on that anxious energy. But an even bigger difference is that a genuine one-take film has a weird languor about it. Simple acts, such as walking from room to room and driving from one location to another take place in real time, and that creates more immediacy. We’re forced to inhabit spaces in a more direct and immediate way.”

I think he’s right. If done the cheaper, easier way by faking a single-shot episode or using the standard wide shot/medium shot/close-up editing techniques, Adolescence might still be a good show, but it wouldn’t be extraordinary — which it certainly is.

That said, Apple’s new The Studio is more in my wheelhouse these days. Two episodes in, I love it — and you don’t have to be a Hollywood veteran to appreciate this show. It’s cringy-worthy in the extreme, but very funny … and I don’t know about you, but “very funny” is exactly what I need right now.

****************************************************

So here we are, May already, the doorstep of summer. It’s easy to be overwhelmed by the tsunami of bad news these days: we’re in a serious shit-rain with no end in sight and the news brings another “unprecedented” insult every day. I don’t know how, when, or if this will end, but here’s the crux of the test facing each of us: Do we remain strong, keep the faith, and push back however and whenever we can to set things right, or do we curl up in a fetal position and hope that it all goes away?

Time will tell.

PS: if you haven’t been reading Too Much Film School … well, you should start. Hint: it’s not about film school.

…

I guess when a film becomes a classic, we do tend to think that it came off without a hitch. It's too perfect for any major obstacles to have been in place during production. I don't know why we do this. Haha. I don't think anything gets done without a lot of sweat and blood and grunts and agony at times. The world is just a tough place, even in the world of fiction. I think the single-shot take is a good gimmick and having a whole movie or series done that way is an exceptional feat. I recently watched a film from the 50s called The Thief, I believe, where Ray Milland was the star and there was absolutely no dialogue in ninety minutes. I kept waiting but it never came. It's a fine film and again, I enjoyed the gimmick here as well. However, I do believe that overall, a gimmick is not a great thing for a long work, whether it be movie or series. Having shots that go on for ten or fifteen minutes with no cuts is awesome but like any gimmick, too much of it becomes tiring and flat-out annoying. Very interesting post, though. Thank you for sharing, Michael.

Thanks for the pointers to some entertainment. Gawd, do I need it! Happy spring 💐