The first of a short series from the archives, dusted off and reworked for modern times.

“This job is a piece of cake,” said the voice on the phone, a gaffer I’ve known for a very long time. “The DP is a great guy who knows what he wants and doesn't try to reinvent the wheel every week. Most of the episodes only have one swing set, and sometimes not even that — our last three shows didn’t have any swing sets at all.”

Given that lighting swing sets is where the heavy lifting is done on a multi-camera show, this sounded like the easiest sitcom money I’d ever make. Not very much money, mind you, since working under a $650,000-per-episode cable contract means getting paid the much-reviled “cable rate” by a production company under relentless pressure from their corporate overlords to wring every last drop of blood from the budgetary turnip.* Unlike my last show, there would be no 48 hour weekly guarantee for moi: instead I’d get the industry minimum eight-hour day plus overtime for any additional hours worked, and that’s all. Combined with the 20% below-scale insult of cable rate, this translated into a $300 pay cut, but with my old show gone and maybe/maybe-not coming back at some vague point in the future — and nothing else on the horizon — I was ready to take anything short of a 4/0 rigging call.** If nothing else, this job would keep my head above water for the entire month of January without seriously kicking my ass.

The latter means a lot at this late stage of my career, so I signed on.

The show is another product of Disney’s assembly-line comedy machine, churning out simple-minded sitcoms for an audience of kids between six and twelve years old. Most of the cast is well under eighteen, but as the first week unfolded, I was surprised how good they were in front of the cameras. True, we’re not exactly making “Hamlet” here, but these kids fully inhabit their roles and bring a lot of energy to the set. They've got talent, all right, and it's clear that they'll be making buckets of money for the Disney Corporation over the next few years.

Those of us toiling below-the-line won’t do nearly so well, but the awkward truth is that the low pay had everything to do with my getting this job in the first place. A slot on the crew was open only because the Best Boy hasn’t been able to keep a crew all season long. His juicers would stay if the show paid scale, but the minute one of them got wind of a better-paying job, he or she was gone.

The first week came as advertised, with just one small swing set resulting in three short and easy lighting days. The block-and-shoot day went twelve hours, but that involved a lot more waiting than working, and the shoot night was done in just ten hours. Our DP is a sweetheart: calm, polite, and a very nice guy — and more to the point, he’s clear and decisive when it comes to lighting the sets. Equally important, he understands what matters and what doesn’t, and the meaning of the phrase "Don’t put your foot through a Rembrandt." I’ve worked for him in the past, and always enjoyed the experience, which is one reason I took this gig. In many ways, he’s the polar opposite of the DP I just did 45 episodes with — a man with a similarly great eye, but whose frantic, ceaseless tweaking of the lighting earned him the nickname of “The OCDP.” He’d bolt out onto the set like a Polaris missile twenty times a day to have us add a scrim to a lamp, take it out, pan the head a quarter inch to the right, then put the same scrim back. He’d then stare at his light meter, shake his head, and dart back into the Bat Cave.***

There’s none of that on this show, which made it a lot easier to say “yes” to the job.

The gaffer is a very old friend I’ve known since we were in school together, but if there’s one thing you can count on in Hollywood, it’s the peril of believing anyone who tells you “This job is a piece of cake.” Even if he’s telling the gospel truth as he believes it, when he says “bring a book — you’ll need it,” you can bet this sweet promise will curdle before long. That the previous three episodes didn’t include a single swing set between them — three simple “bottle shows” in a row — meant nothing, because past is seldom prologue in a business where the only guarantee is that there are no guarantees.

That first week was indeed a piece of cake … and the calm before the storm. As I drove home Friday night, I had no clue that the easy part of this job was over, or how very different the next two weeks were going to be.

* $650K is a lot of money in the real world, but this is Hollywood, where the average network multi-camera show comes in around $1.5 million per weekly episode. Considering that single camera comedies and episodic drama cost two to three times that, mulit-camera shows are considered a bargain in the upside-down world of television. Even my old show — a low budget cable-rate operation from top to bottom — was made on a $900K per episode contract, which gives you an idea just how cheap Disney really is.

** A friend of mine, younger than me, but no Spring Chicken, took a 4/0 rigging call last year during which his crew wrangled seven hundred pieces of 4/0 — that’s 35 tons of cable — through a mountainous canyon for the movie “Super Eight.” The poor bastard won’t make that mistake again.

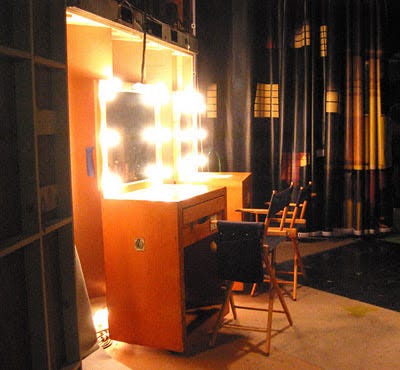

*** The “Bat Cave” is what we call the dark, closet-sized room where the DP and a Digital Imaging Technician sit all day staring at a $27,000 ultra high-def OLED flat screen monitor displaying the feeds from all four cameras.

Nicely done