(This is the third in a four-part series exhumed from the archives that begins here.)

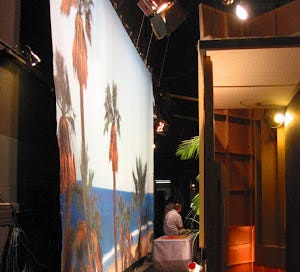

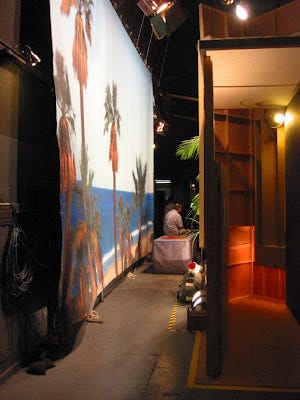

A front-lit canvas backing hung against the stage wall behind the four-foot zone

If week two was bad, week three was worse. Much worse. The construction crew began building two swing sets over the weekend, a big interior and a much larger exterior that was quite literally a jungle, complete with rainforest backing and four hundred large potted plants. The jungle set wasn’t so bad — in general, bigger wide-open sets are easier to light, enabling us to use larger lamps hung further away. Not only does this work with (rather than against) the immutable laws of the Inverse Square, but using a few big lamps is often less time-consuming than hanging (and powering, adjusting, and tweaking) dozens of smaller units.*

Although the big jungle set was reasonably user-friendly, the interior swing set — a houseboat destined to sink — was another story, built atop a three-foot-tall platform of “steel deck” to allow the special effects crew sufficient room to install their rigs underneath. This meant that our man-lifts could only work around the perimeter, leaving the bulk of the lighting to be done from ladders on the elevated set, along with an absurdly cumbersome construction lift that was just light enough to avoid damaging the set floor, but heavy enough to require a forklift to get it up on the deck. Adding to the confusion, these two big swing sets took up all the remaining space on an already crowded stage. With very little room to store our yet-to-be-deployed lighting gear, we were tripping over ourselves and everyone else all week. While threading his way through the mess, one of the grips stopped to survey the scene, then shook his head.

"This is ten pounds of shit in a five-pound bag," he sighed.

Still, our job is to light the set — which we did — and at least there were good reasons for the way both these sets were built. This is not always the case ... which brings me to a pet peeve of sorts, a sharp little stone that’s been festering in my shoe ever since I moved into the world of multi-camera shows. We rarely had problems lighting soundstage sets during my twenty-plus years of working single-camera productions for one reason: our set designers factored in the needs of other departments when drawing up their blueprints. If only this held true in the multi-camera realm, where set designers seem to live in their own little world unencumbered by any concerns for the rest of the production. I don't expect them to figure out how the sets should be lit — that’s our job — but as the saying goes, "If you can't help us, at least don't hurt us."

An inexperienced set designer might be forgiven for not allowing enough room behind sets to properly light a backing — once — but the rest of them are seldom any better.** When I asked about this early in my multi-camera journey, the reply was that the main concern of sitcom set designers was creating big beautiful sets that make great photos for their “book” — a portfolio used to get future work — rather than crafting user-friendly sets for the show. Trouble is, that book never reveals how little of the sets actually ended up on screen for the show.

Multi-camera sitcoms are all about people talking, which mostly means two shots and three shots, then moving in for an occasional medium shot or close-up on a punchline to get the big laugh. A typical multi-camera show rarely goes wider than a four-shot to open a scene, then goes in to cover the rest — they don't do car chases, big explosions, or rock-'em-sock-'em fight scenes requiring huge sets or extremely wide shots.

So why build sets with enormous bay windows that add nothing to the show, but cause endless reflections to bedevil all four cameras? Why build entrances and alcoves with low overhangs that are never seen on camera and where lamps can’t be hung — and while I’m on my soapbox, once a set is finished and lit, why the hell do set decorators then hang giant chandeliers (usually the night before shoot day) in a living room and/or dining room set, invariably blocking the back-cross key lights that are the foundation of multi-camera lighting?

You know the answer as well as I do: "Because that's the way we’ve always done it." To quote the question posed by a Bud Light ad campaign back in the early 90’s: Why Ask Why?

A set should be big enough for an especially creative (ahem...) director to work, but that's no excuse for needlessly complex and fussy set design that owes more to the designer’s professional ambition than the actual needs of the show. If those elements of a set are written into the script or otherwise help propel the story, fine — but most of the time the problems we end up having to solve are caused by set designers blithely unaware that other departments also have work to do. I can only assume they just don’t care.

I don't understand that attitude. While lighting a set, we consider how our lamps might affect sound (will a lamp cause boom shadows?), the grips (do they have enough room to effectively cut and shape the light?), and camera — will a given lamp impede any of the four cameras or in any way impinge on the shot? From what I've seen, it's a rare multi-camera set designer or decorator who gives any thought whatsoever as to how their work impacts other departments.

In a way, I can’t blame them — after all, we always manage to pull a rabbit out of the hat and get the sets lit no matter what, so why should they change their oblivious ways? It’s the consistently smug, self-serving myopia of these clowns that pisses me off — so yeah, I do blame them.

Okay … that's off my chest. End of rant.

Getting those two swing sets lit was a struggle, but we got it done despite the difficulties. The only truly good thing about week three — the final week of production — was that after a 14 hour Thursday and Friday night’s 15 hour day, we were able to walk away. With a full week to wrap the stage commencing the following Monday, our only responsibility that night was to “make it safe”: lower any lamps on stands, clear the four-foot zone around the perimeter of the stage, and plug in the man-lifts — then go on home.

Which is exactly what we did, and grateful though I am for these past three weeks of work, I’m really glad this one is almost over.

* Here’s a much more entertaining and visually effective demonstration of the inverse square at work.

** Cloth backings, once the industry standard, are usually front-lit, while trans-lights require backlight, but many modern digital backings utilize both — front-lighting for day scenes, back-lighting for night.

As a now 15 year veteran of sitcom’s, I understand the frustrations of the technical crew able to easily execute their duties because of set design that doesn’t take into consideration,Grip, electrical and sound. Thinking of my last sitcom, which I worked on for a few seasons, our Dp was always part of the conversation and I believe those issues were greatly mitigated. Sometimes it takes a second season to dial in those issues. Thanks as always for your commentary Mike.

I thought the whole point of using a set designer was to have someone on the team who understood image, illusion and all the technical requirements of all the departments; someone who could avoid unnecessary production costs whilst providing inspiring environments for the actors and director to develop the story.

At least, that's what I was taught. 🤣

Loved the butter gun and hey, I learned something new today. Thanks, Michael!